Uncontacted tribes aren't 'Stone Age.' They just want — and deserve — to be left alone

© Survival International

© Survival InternationalA verison of this article appeared in the LA Times on December 16, 2018

Uncontacted tribes show clearly that they want to be left alone. Forced contact is not only dangerous to the tribes and those who contact them, it is unethical.

© Survival International

© Survival International

The death last month of Christian missionary John Allen Chau, at the hands of the uncontacted island tribe he had hoped to evangelize, triggered a thorny debate. Was the Indian government, which oversees North Sentinel Island, keeping the people of this tribe in a glass museum box or protecting their freedom? Some scientists assert that uncontacted tribes cannot survive without some intervention from outside. Another school of thought considers it unfair to “deny” the Sentinelese the benefit of cellphones and schools.

The hubris of that belief — that uncontacted tribes are somehow missing out if they lack electronics and algebra lessons — is wildly out of step with the message that these tribes have been sending all along: They want to be left alone. And they must be. Forced contact is not only dangerous to the tribes and those who contact them, it is unethical.

Survival International estimates that there are more than 100 uncontacted tribes similar to the Sentinelese. Although they may shun contact now, many of these groups have had limited interaction with the outside world in the past, enough to know that they don’t want more. Most uncontacted groups live in South America, and there is also thought to be a number in the forests of New Guinea.

© G.Miranda/FUNAI/Survival

© G.Miranda/FUNAI/Survival

Far from being the exotic “lost tribes” of sci-fi or legend, these uncontacted tribes are simply self-sufficient peoples who seek isolation from the dominant society. Some like the Sentinelese actively repel outsiders; they wave weapons, shout and, in extreme situations, kill those, like Chau, who insist on making contact. Others simply hide. They aren’t Stone Age, nor are they living a lifestyle that’s thousands of years old.

The limited contacts we have had indicate that these remote societies change and innovate, just in different ways than the industrialized world. Younger generations build on existing knowledge, devise more effective tools and techniques, often using and adapting outside goods for their own purposes. These are best understood as contemporary societies with a different way of life. Their members make homes, love their families, tend the landscape, and like all of us, want to live well and in peace.

© G. Miranda/FUNAI/Survival

© G. Miranda/FUNAI/Survival

They do not lack sophistication or expertise. Their hunter-gatherer lifestyles require vast botanical and zoological knowledge and a unique understanding of sustainable living. Brazil’s Awa tribe, some of whose members have left their traditional home in the Amazonian rainforest, identify and use 275 plants and 31 species of honey-producing bees.

The Sentinelese and a neighboring group, the Jarawa, were virtually unharmed after the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami in 2004 that killed 225,000 people in the same region. The Jarawa said later that they knew to get to high ground as soon as they saw the tide recede quickly.

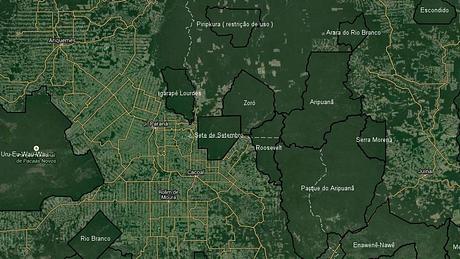

The tribes’ isolation benefits the environment as well. There is irrefutable evidence that their territories in the Amazon are barriers to rainforest deforestation — satellite photos reveal stark images of Indigenous reserves as islands of green surrounded by denuded Earth.

© Google Earth

© Google Earth

Chau’s death may lead some to consider the Sentinelese as savages. In reality, like the other uncontacted tribes, they are the most vulnerable people on the planet. Their societies are at risk of being wiped out by violence from outsiders who want their land and resources, or who bring with them diseases like the flu and measles to which the tribes have no resistance.

In many cases, it’s likely that a previous traumatic experience with the dominant society, either in living memory or passed down through generations, led these groups to choose isolation. In the case of the Sentinelese, there is speculation that previous contact brought disease. In western Amazonia, uncontacted peoples are often the descendants of the few survivors of the rubber boom at the end of the 19th century, when 90% of the Indigenous population was wiped out in a horrific wave of enslavement and brutality.

Even under the best of circumstances, contact has proved dangerous. Brazil’s Department for Indigenous Affairs conducted “first contact” expeditions in the 1970s and 1980s. One of the most experienced expedition leaders, Sydney Possuelo, said: “I set up a system with doctors and nurses. I stocked up with medicines to combat the epidemics which always follow. I had vehicles, a helicopter, radios and experienced personnel. ‘I won’t let a single Indian die,’ I thought. And the contact came, the diseases arrived, the Indians died.” The expeditions were abandoned.

When Survival International was established in 1969 to advocate for the rights of tribal peoples, many claimed it was inevitable that uncontacted tribes would die out soon or integrate into the mainstream. Yet they still exist, and where their rights are respected, they thrive.

In large parts of the Colombian rainforest, for example, the relative lack of outsiders means that uncontacted tribes there can live in comparative peace. In Brazil, by contrast, there has been relentless pressure from loggers and ranchers for many years, reaching into the farthest corners of the Amazon, a process that is likely to accelerate with the election in October of President Jair Bolsonaro. He has said that he will reject new land claims by Indigenous peoples and wants to open the land already reserved for them to mining and farming operations.

The key to stopping uncontacted tribes’ annihilation is protecting their land rights, which are enshrined in national and international laws, like the one Chau broke when he made his way to North Sentinel Island. The Sentinelese and their counterparts are our 21st century contemporaries, and a vital part of humankind’s diversity. They have the right to live as they choose — unbothered by the rest of us.

__________

More than 150 million men, women and children in over 60 countries live in tribal societies. Find out more about them, the struggles they face, and how you can help – sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.